Introduction. Blockchain. Everything is a contract. Types of messages. Gas.

Everscale (hereafter ES) was created on the basis of the whitepaper and initial code of the TON (Telegram Open Network) project from Nikolai Durov. Essentially, the blockchain repeats the behavior described in this whitepaper: https://ton.org/tblkch.pdf , however, not everything works as is presented in the whitepaper.

The Everscale Philosophy

In order to introduce the tutorial, we would like to speak about the Everscale blockchain and what makes it so promising.

When Nikolai Durov was creating TON, he was faced with the task of designing a blockchain platform that could accommodate millions of users while having low, stable transaction fees.

Durov was able to achieve this, and this is how:

- Infinite Sharding.

On ES shards are dynamically added as the load increases and then merged back. This is possible because all contracts on the chain communicate with each other asynchronously, and therefore we can split one shard into two shards without any problems occurring. (Shards are just divided in half according to the ranges of contract addresses.)

- Rejection of radical decentralization.

The ES blockchain was not built to allow just anyone to become a validator. Validation is a critical process, requires professional equipment and access to an appropriate server. The total number of validators will at most be in the thousands, not in the tens of thousands. And validator machines have high server and channel requirements (the current requirements are 48 CPUs, 128 RAM and 1TB SSD) and a 1GB channel (the network is used extensively). This allows for the blockchain to support a very quick block release speed and often rotate validators in the shards.

- Paid storage.

This is a completely brilliant and daring decision that no other blockchain has implemented.

When you write something on a classic blockchain (like Ethereum), you put information on the chain forever.

So, if you buy a meme coin, data reflecting that purchase will be on the chain until the chain dies. You only pay on creating and accessing that information. However, validators must store that information forever.

This give rise to a curious economy - blockchains are forced to artificially limit their rate of recording so that the size of the blockchain state does not grow faster than the rate at which data storage becomes cheaper (In fact, they are even forced to try and prevent the blockchain state from growing faster than the rate at which RAM becomes cheaper). As a result, users are forced to compete with each other in auctions for the right to write data to the blockchain, and transaction fees are increasing all the time.

On ES, this problem is solved very simply - each contract is required to pay rent for the validators to store its state, and when the contract runs out of money, it gets deleted. Yes, this is radical, by doing this, users do not need to compete with each other for the right to write indelibly on the blockchain. On ES, each user determines how long they want their data to remain on the blockchain and has the option to extend that time frame. This makes the tokenomics of the chain completely unique, adding flexibility to the data inputed to the chain.

Essentially, ES aims to be a decentralized replacement for AWS. Just as you can host your application on AWS, you can host it on ES. Hosting it on ES will not be much more expensive (if it is rarely used, it will be cheaper), but it will have maximum fault tolerance.

Blockchain

This tutorial is not going to delve into the details of how exactly the ES blockchain works, because you don’t need all of that to understand how to write smart contracts for ES. In the course of the tutorial, we will analyze the guarantees that the blockchain gives and everything you need to know to write smart contracts.

What do you need to know about the blockchain? ES is a multithreaded blockchain. There are different work chains (like global shards, they differ in parameters—there are 2 of them now), and the work chains are further divided into processing threads (like shards, just different validators execute transactions in different smart contracts in parallel, they are added dynamically with increasing load and then deleted).

But what you really need to know is that you don't have to think about where your smart contracts are. All communications between contracts are asynchronous via sending messages. It doesn’t matter if two contracts are in the same processing thread or even in different workchains, any call to another contract is a message being sent, and if you are waiting for a response, it will come in another transaction.

Everything is a smart contract!

On Ethereum, there are two built-in types of accounts: contract accounts that are deployed to the network and externally owned (wallet) accounts that are controlled by anyone with private keys and can initiate transactions. On ES, there are only contracts, there are no built-in contracts in the form of wallets on the blockchain. A wallet is just a smart contract, and there are many different kinds. Transaction chains on ES can be started by any contract with the help of an external message (if the contract supports receiving external messages).

Transactions are started when a smart contract receives a message. During a transaction, a contract can send as many messages as it wants to another contract. (Once received, these messages will begin another transaction).

There are two types of messages:

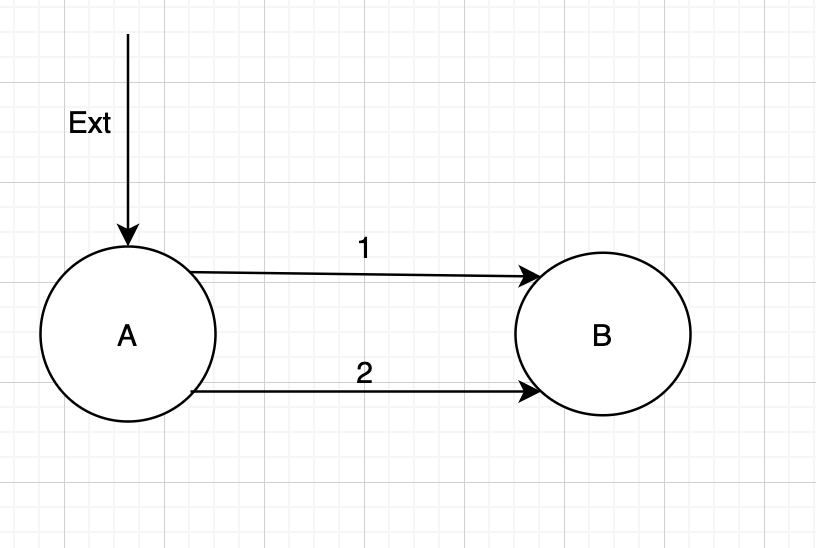

External message

A message from nowhere or to nowhere :-) This kind of message has only a destination address or a sender’s address. Primarily, this kind of message is used to call contracts from the outside world ( from programs or wallets ). This is a fairly unique concept that allows any contract to start a chain of messages.

External messages work like this: you send a message with data from nowhere to a contract.

A validator allocates 10k of gas credit to this message, and attempts to complete the transaction by calling the contract and passing your message to it. The smart contract must agree to pay for the transaction from the contract account by calling the tvm.accept() method before it runs out of gas.

If this method is called then the transaction continues and the contract can create other outgoing messages.

If an exception occurs or the contract does not call tvm.accept() or the gas credit runs out, then the message does not go to the blockchain and is discarded by the validator. (In simple terms, a message cannot get into the mempool if it cannot be successfully added to the blockchain).

Interestingly, an external message can contain any data and does not have to contain a signature. (For example, you can make a contract receive an arbitrary message every minute from anyone you’d like and as a result perform some kind of action, like a timer).

Here is an example of a simple wallet smart contract, which can only transfer money after receiving an external message:

pragma ton-solidity >= 0.35.0;

// This header informs sdk which will create the external message has to be signed by a key.

// Also directing the compiler that it should only accepted signed external

// messages

pragma AbiHeader pubkey;

contract Wallet {

constructor() public {

// We check that the conract has a pubkey set.

// tvm.pubkey() - is essentially a static variable,

// which is set at the moment of the creation of the contract,

// We can set any pubkey here or just leave it empty.

require(tvm.pubkey() != 0, 101);

// msg.pubkey() - public key with which the message was signed,

// it can be 0 if the pragma AbiHeader pubkey has not been defined;

// We check that the constructor was called by a message signed by a private key

// from that pubkey that was set when the contract was deployed.

require(msg.pubkey() == tvm.pubkey(), 102);

// we agree to pay for the transaction calling the constructor

// from the balance of the smart contract

tvm.accept();

}

function send(address dest, uint128 value, bool bounce) public pure {

// we check that the signature of the external message is right

require(msg.pubkey() == tvm.pubkey(), 100);

// we aggree to pay for the external message from the contract balance

tvm.accept();

// everything is simple here, we create an outgoing message

// internal message which carries the value nano evers

// bounce - a flag, which tells TVM what to do if dest contract

// does not exist or throws an exception on our internal message.

// bounce - true - this will try to create a return message to us with an error

// and the remaining money (if there are enough funds to create a message),

// bounce - false, this will leave the funds there.

// 0 - the flag of message creation, we will get to that later.

// 0 means that with the message we have to send value EVER

// and pay the fee for the creation of a message from that value.

// (by sending a little less than the value)

dest.transfer(value, bounce, 0);

}

}

Internal message

Internal message. This is always a message from one contract to another. This kind of message always has to carry a certain amount of EVER with it because when another contract is called, there is no gas credit like in the previous case with an external message, and before calling tvm.accept(); (if this occurs) gas will be paid for from the VALUE attached to the message. If the EVER value cannot cover the gas fees, the transaction will fail.

dest.transfer(value, bounce, 0); - This is the creation of an internal message with the value sent which will call the receive() function of the receiving contract without any kind of data.

contract Receiver {

uint public counter = 0;

receive() external {

++counter;

}

}

Important Concept

On ES, there are guarantees for the delivery and order of internal messages on the blockchain protocol level.

If you send a message, it will be delivered.

If contract A sends two messages to contract B, they will be delivered to contract B in the order in which they were sent from contract A. It does not matter whether the messages were sent via one transaction or via different transactions.

Gas.

We are not going to cover the exact formulas here, these are available from: https://docs.ton.dev/86757ecb2/v/0/p/632251-fee-calculation-details

We will just cover what you need to know and what you are paying for.

Firstly, the gas price is a network parameter, and the price does not change on its own as a reflection of demand at a given moment.

In the future, it is planned to introduce a mechanism for controlling gas prices. Most likely, this will be realized with the establishment of a hard-capped maximum gas price (the current price) and a possible lower price which would be applied if the demand decreases. Gas price will be hard-capped because on this blockchain it is critical for users to be able to calculate the exact maximum amount of tokens that they will have to spend on any action. (Due to the asynchronous model employed, you have to be able to know how much money to attach to a message so that you can send enough to cover all transaction fees in the long sequence of messages)

We pay for:

- Computing, the same as other blockchains.

- Loading memory cells, which is quite different from how things work on Ethereum. We will cover this in detail in the chapters on tvm and boc.

- The creation of outgoing messages, and we pay for an incoming messages if they are external and we agree to pay for them.

- Storage. Every contract pays a rental fee for the storage of its own code and its state data. This fee is withdrawn each time a message is sent to you (for all the time that has elapsed since the last transaction). If the balance of your contract falls below 0, the further calls to the contract will cease to work until you replenish the balance. If the balance falls below -0.1 EVER (for workchain 0, a network parameter, can be changed) the contract will be frozen, with only the hash of data and code remaining while everything else is deleted. The unfreezing process is complicated, you need to replenish your contract and provide its data and code the moment it is frozen. In theory it is even possible that the hash gets deleted, if the contract is left frozen for a while. So you don’t want to store inessential information on the blockchain even though writing on the chain is cheap, as we pay for storage on the chain separately. In the chapter “Distributed Programming” we will look at how we should organize our smart contracts in accordance with the “paid storage” paradigm.

The next part of this tutorial will cover what we need to know about TVM and the format of storing data on the blockchain.